Visualizing Abiyoyo

Pete works with Michael,

turns his storysong

into a picture book.

Pete's challenge: illustrate this story's giant message.

Pete's response to Michael's Abiyoyo book proposal came with a cautionary note:

"Several artists have tried to make a book of Abiyoyo, but we turned 'em all down."

Sending Pete the Abiyoyo picture book proposal

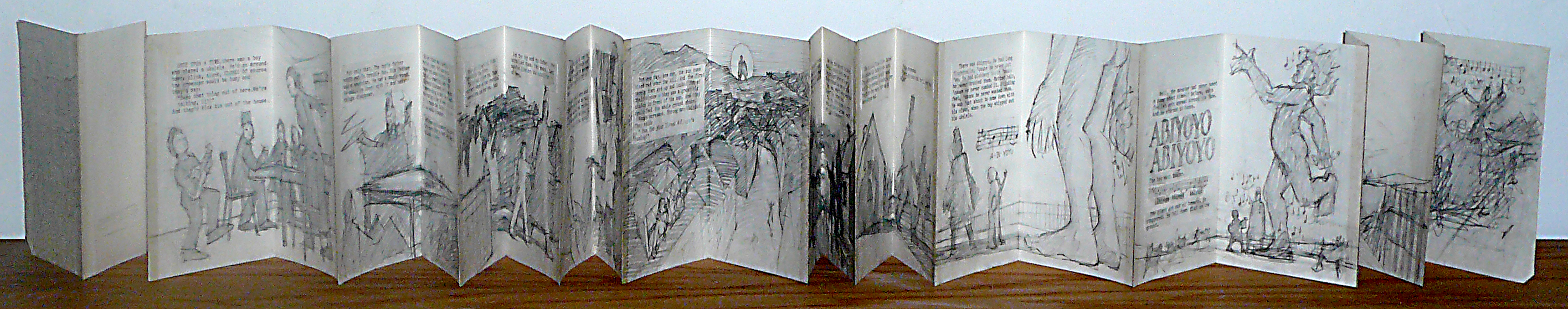

Michael had been working as a high tech computer graphics artist at a giant corporation, but wanted to illustrate children's picture books. Michael needed to show off his illustration and design skills to prospective publishers. He found inspiration in Pete Seeger's music and stories. He sketched out Pete's story of Abiyoyo and mocked it up as a little book using a text Pete had published in Sing Out! Magazine in 1964. Michael included this Abiyoyo book dummy in his illustration portfolio–one part of a sales pitch to solicit freelance jobs from art directors at New York City publishers.

Art directors liked this acordian style Abiyoyo book dummy. "You should publish this!" Michael had no idea whether Pete Seeger would be at all interested. A phone call to the Clearwater Organization turned up his P.O. Box number. He sent Pete a larger, revised version of his book proposal in March of 1981. Pete worked hard to keep up with the deluge of mail he received. In just a few weeks Michael received Pete's response to his proposal with a personal letter.

Making an Abiyoyo picture book

Michael was the first artist to send Pete a complete book mock-up of his story. Pete liked that Michael was more of a painter than a cartoonist, but he saw some big problems with making Abiyoyo into a picture book. How can they be true to the story's African origins? How can they design the giant's visual character in a way that was relavent to today's real world?

Pete challenged Michael to solve these problems. Pete wanted lots more pictures of the giant dancing. Michael had only sketched a single page of Abiyoyo dancing. Pete wanted as many images of the dancing giant as possible. Michael had only sketched one of the father's magic tricks. Pete wanted all 3 of the father's magic tricks to be illustrated!

Abiyoyo's African origins

Pete had adapted his story from a South African folkstory, but Michael had not been thinking about the story's African origins or the ethnicity of his characters. Pete wanted the boy and his father to reflect the African origins of the tale. They agreed that the boy and his father in their book would be Black characters. Michael's initial sketches showed the magician father wearing a top hat and tails. Pete nixed this European style stage magician get up, and they improvised a new costume for the father.

A surreal setting for Pete's story

Should the little town in their picture book be set in South Africa? Should all the townspeople be African? Pete wanted to broaden the setting of their the book and convey a more universal message. Pete had the notion that the townspeople could appear to be from all over the world–a global village. Michael's illustrations ended up looking like a surreal allegorical fable. Each of the many townspeople represents a nation or ethnicity, but these characters seem mearly symbols of various peoples. They lack individual character development and personality.

At the center of the story and standing out in contrast to the townspeople are the Black father and son, and the giant Abiyoyo. These characters each demonstrate talent, personality, and have a strong story arc. The story narrative follows their relationships with the townspeople as they suffer rejection, crisis, and a chance to display their courage and creativity.

One of Michael's early concept sketches for Abiyoyo

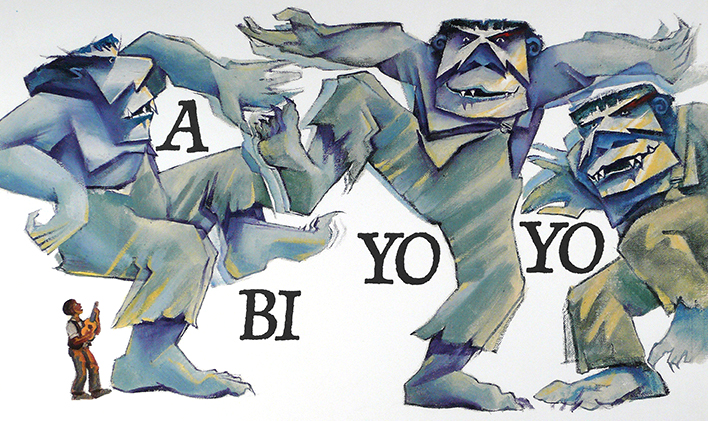

Our greatest challenge–illustrating the giant's character

Pete was not at all satisfied with Michael's first sketches of the giant. He had sketched the giant as a big man with long shaggy hair (and he drew him without any clothes)! Pete insisted that a naked giant would not be OK for a little kid's story. So, Michael drew overalls on Abiyoyo. He responded to Pete's crtiques, drew new sketches, and Abiyoyo's appearance evolved.

"I think Abiyoyo is not a man or an animal," Pete said, "but a man-made giant. Think about Frankenstein's monster."

Pete sketched out his own version of Abiyoyo with a ball point pen. "He has little pig eyes, thin lips and pointy teeth." Maybe Abiyoyo could look like a Sesame Street muppet, Pete suggested.

He sent Michael an abstracted potrait of Hitler by illustrator Marshall Arisman. "Maybe your painting style for Abiyoyo could look more like this."

Pete told Michael to look at Picasso's cubist paintings and the carved wooden African masks which inspired Piccasso's work.

"Thinking of Piccasso, I stacked cubic shapes to build my blockhead Abiyoyo, Michael recalls. "This dynamic visual concept–a character whose appearance completely changes as his mood changes–seemed promising, but Pete thought that as this Abiyoyo gets happy, he looked too much like a clown."

"Make him look more scary," Pete insisted. Back to the drawing board.

Michael began to produce dozens more sketches, stretching and squashing Abiyoyo's face. He began using jagged shapes. He mixed up the cubes in Abiyoyo's face so the edges did not really fit together, as if the 3 dimensions were scambled, a better attempt at cubist stylings. The Abiyoyo you see in the published book finally began to reveal himself.

Visiting Pete and Toshi

Most of Michael's collaboration with Pete happened via US snail mail and telephone conversations, but he also rode the train up from New York City to visit Pete and his wife, Toshi, in Beacn, NY. Michael's first visit gave Pete and Toshi a chance to look through his professional art porfolio and to review his full color illustration work. Pete arranged to bring Michael over to visit a nearby kids summer camp were Pete had performed over the years. He wanted Michael to see the latest version of his stage performance of Abiyoyo, which had become more dramatic and expressive than the early recordings Michael was familiar with.

A second visit came only after years of work, discussions, new drawings, revisions and more revisions. Eventually Michael presented his (mostly) finalized drawings. Pete gave him the go ahead to negotiate a contract with a publisher. Up to this point all Michael's work had been without compensation or contract. "It was wonderful to work with Pete in my spare time," Michael explained, "but we needed a publisher to fund the project." Their work eventually stretched over 5 years from Michael's first sketches to his finished full color art.

A rookie illustrator's first contract

Michael asked Dilys Evans to be his professional representative and negotiate a book contract with Macmillan Publishers. Michael first met Dilys at Rhode Island School of Design. She had been working as art director of Cricket magazine, but began working as an illustrator's agent in the children's book market and was actively seeking young aspiring illustrators. Dilys hammered out a contract which provided Michael the advance he needed to begin working full time on his Abiyoyo artwork. Dilys Evans continued to represent Michael's professional interests in children's book publishing for the next 25 years.

Michael's Red Hook, Brooklyn studio

The long hours required to produce full color paintings for Abiyoyo was at hand. More revisions and changes were in store. Michael rented a loft space above a woodshop where some friends produced custom furniture. From his apartment in Cobble Hill, Brooklyn, he had a short commute across a Brooklyn-Queens Expressway overpass to his studio. This part of Brooklyn's Red Hook neighborhood had suffered serious decline. The BQE had cut this enclave off from the surrounding neighborhoods. Most of the buildings for a few blocks around Michael's studio had been boarded up or torn down. He spent the next year and a half working in his Red Hook studio, finalizing all his drawings, stretching canvases, mixing oil paints and gradually putting all the pieces of the picture book puzzle togther.

I, I, I, Aint Gonna Play Sun City

By the time Michael was creating his final full color art for his Abiyoyo picture book, the South African freedom struggle had gained the popular support around the world. Check out the many rock and rap recording artists appearing in this music video:

Artists United Against Apartheid - Sun City.

Reading Rainbow...